-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Barkat Masood, Peter Lepping, Dmitry Romanov, Rob Poole, Treatment of Alcohol-Induced Psychotic Disorder (Alcoholic Hallucinosis)—A Systematic Review, Alcohol and Alcoholism, Volume 53, Issue 3, May 2018, Pages 259–267, https://doi.org/10.1093/alcalc/agx090

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

To evaluate the effectiveness of evidence based treatments for alcohol-induced psychotic disorder (AIPD) as described by ICD-10 and DSM-5, a condition that is distinct from schizophrenia and has a close relationship with alcohol withdrawal states.

Systematic review using PRISMA guidelines.

Of 6205 abstracts found, fifteen studies and ten case reports met criteria and were examined. Larger studies examined the use of first-generation antipsychotic drugs, reporting full or partial remission in most patients. Newer case reports report similar results using second generation antipsychotic drugs. Novel treatments, such as those acting on GABA receptors reported low numbers of patients in remission. Some large studies report the successful use of standard alcohol withdrawal treatments.

The findings of our systematic review are inconclusive. There was significant heterogeneity between and within studies. Significant publication bias is likely. Randomized control trials of more carefully delineated samples would produce evidence of greater clinical utility, for example, on differential effectiveness of antipsychotics and optimal length of standard alcohol withdrawal treatments. AIPD patients who show poor treatment responses should be studied in greater depth.

This systematic review of alcohol-induced psychotic disorder treatment found 15 studies and 10 case reports of relevance. Older studies of first-generation antipsychotics reported full or partial remission in most patients, as did newer studies with second-generation antipsychotics. Novel drugs reported low remission rates. Standard alcohol withdrawal treatments were successful.

BACKGROUND

Excess alcohol consumption results in medical and social problems around the world. It accounts for 3% of global deaths (Rehm et al., 2009). Neuropsychiatric consequences to alcohol dependence syndrome include delirium tremens, alcohol-related brain damage, Korsakoff’s syndrome and alcoholic hallucinosis. The terms ‘alcoholic hallucinosis’ and ‘alcohol-induced psychotic’ disorder (AIPD) are often used interchangeably, although they may be better regarded as over-lapping categories. In this review we follow ICD-10 (WHO, 1992) in using the rubric AIPD to include both syndromes (ICD-10 code F10.5, corresponding to DSM-5 code 292.1).

According to ICD-10 (WHO 2016 version), AIPD is a condition where mental and behavioural symptoms manifest within 2 weeks of alcohol use and must persist for more than 48 h. Symptoms should not arise as part of alcohol intoxication or an alcohol withdrawal state. Clouding of consciousness should not be present to more than to a minor degree. An episode can persist for up to six months. A wide variety of symptoms can occur, including schizophreniform delusions, hallucinations, depression and mania. DSM-5 (American Psychiatric Association, 2013) specifies that the substance should be capable of causing symptoms and that the condition should not be better explained by another psychotic disorder.

There are a number of assertions made within the AIPD literature. In a Finnish study, AIPD was found to have a general population lifetime prevalence of 0.41%, or 4% for people with alcohol dependence syndrome. It was most common amongst men of working age (Perälä et al., 2010). AIPD is said to manifest immediately after the consumption of large amounts of alcohol. It may not be related to duration of alcohol dependence syndrome (George and Chin, 1998; Perälä et al., 2010). Symptoms may develop during alcohol intoxication or withdrawal or soon thereafter. The diagnosis cannot be made until clear consciousness is restored. AIPD is said to usually resolve within 18–35 days with antipsychotic and/or benzodiazepine treatment (Vicente et al., 1990). A minority of patients may have persistent symptoms for 6 months or more (Benedetti, 1952; Burton-Bradley, 1958). AIPD may end through alcohol abstinence alone and return soon after reinstatement of drinking (Glass, 1989b). The assertion that antipsychotic drugs are the treatment of choice (Soyka et al., 1988; Jordaan and Emsley, 2014) is not supported by published randomized controlled trials (RCTs). A number of factors affecting people with AIPD make it difficult to recruit and retain participants in RCTs (Perälä et al., 2010).

There are few rigorous published studies of treatments for AIPD. This systematic review was conducted in order to evaluate the available evidence on treatment.

METHODS

PRISMA Guidelines were used to carry out a systematic review. Medline, EMBASE, PsychINFO, Cochrane and CINAHL databases were searched for studies that had been published between 1 January 1900 and 18 August 2016. Subject search terms were: hallucinations/or alcoholism/or psychoses/or alcoholic psychoses/or chemically induced, drug therapy, prevention and control, rehabilitation, therapy/or alcohol intoxication/or delusions/or delirium/or dissociative disorders. (Search strategy available on request.)

Initial inclusion criteria for screening purposes were articles that:

had been published in any language,

investigated alcohol with or without polysubstance misuse,

investigated hallucinations,

investigated hallucinations attributed to alcohol and polysubstance misuse,

investigated hallucinations that persisted beyond one week of alcohol/drug withdrawal state,

investigated any treatment of symptoms,

investigated any outcome measures,

investigated patients of any age,

were RCTs and

were case reports or series.

There were eight exclusion criteria during the screening phase:

papers that did not have abstracts (Criterion 1),

non-human studies (Criterion 2),

examined acute confusional states/delirium, symptoms that occurred during alcohol/drug withdrawal states of <1 week duration, delirium tremens, drug intoxication states and organic psychoses (Criterion 3),

did not examine hallucinations or psychoses (Criterion 4),

examined schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, mood disorder or delusional disorder (Criterion 5),

did not examine alcohol-related hallucinosis or examined hallucinations due to polysubstance misuse (Criterion 6),

single case studies (Criterion 7) and

did not examine treatment or include outcome measures (Criterion 8).

The minimum standard for outcome measures was classification into no remission, partial remission or full remission.

RESULTS

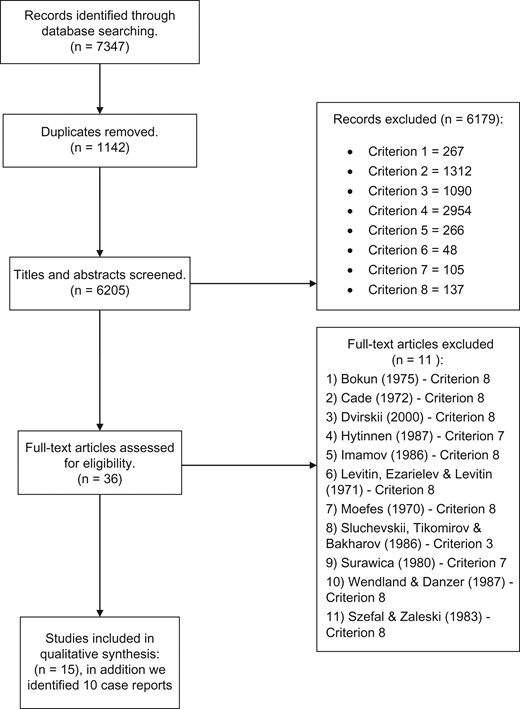

Overall, 7347 articles were identified and 6205 remained after duplicates were removed. Abstracts for the 6205 articles were screened and the 8 exclusion criteria applied. Twenty-six full text articles were requested to assess eligibility. (See PRISMA flow chart Fig. 1.)

In December 2016, a search on the ClinicalTrials.gov (www.clinicaltrials.gov), the ISRCTN Registry (www.ISRCTN.com), the EU Clinical Trials (www.clinicaltrialsregister.eu) and the UK Clinical Trials Gateway (www.ukctg.nihr.ac.uk) websites did not find any completed or ongoing RCTs of treatment of AIPD.

Fifteen studies (for details, see Table 1) and ten case reports (Table 2) on the treatment of AIPD were included in the final analysis. A meta-analysis with funnel plot was not conducted because studies were few and too heterogeneous.

Treatments and Outcomes in AIPD studies

| Author . | Study type . | Treatment and outcome measurement . | Duration (days) . | N, age range . | Outcome: no remission, partial remission and full remission . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gruenberg (1940) | Case seriesa | Electroconvulsive therapy wavelength 7.5 m; 15 min per treatment. Self structured scale of improvement or no improvement. | 5, 6 and 14 treatments. Maximum 28 daysa | Males 3; aged 28–40 | Full remission: 3 (100%)a |

| Bobrov (1966) | Case series (observational study) | Chlorpromazine, antidepressants, psychotherapy. | Unknown | 100 patients | No remission: 100 (100%) |

| Morales-Beda et al. (1968) | Case series |

| 56–252 | Males 6 | No remission: 6 (100%) |

| Entin (1970) | Case seriesb |

| 28–168 | 73 patients |

|

| Boriskov (1977) | Case series (Open label. observational study) | Antipsychotics, vitamin B1 (100–200 mg) and Biyohinol/ Bioochinolum preparation (quinine bismuth iodide) up to 40–50 ml. | 28 | 46 patients | No remission: 46 (100%) |

| Sampath et al. (1980) | Case series (Prospective observational comparison study) |

| Initial period-42 days. Then 546 days. | 30 patients with alcoholic hallucinosis (ICD-9 criteria) compared with 30 patients with paranoid schizophrenia | Alcoholic hallucinosis:

|

Paranoid schizophrenia:

| |||||

| Kabeš (1985)c | Double blind randomized placebo controlled. Crossover trialc |

| 6 | 24 male patients (16 withdrawal states and 8 alcohol hallucinosis) |

|

| Vencovsky et al. (1985) | Case seriesd |

| 2–3 | 35 patients (21 delirium tremens and 14 alcoholic hallucinosis) | Alcoholic hallucinosis: Full remission: 8 (57%). No remission: 6(43%) following parenteral treatment.d |

| Vicente et al. (1990) | Case series |

| 18–35 | 25 (23 males and 2 females) |

|

| George and Chin (1998) | Case seriese | Diazepam 30–40 mg/day. Vitamin B1 (1 ampoule/day) for 3 days, then 200 mg/ day. Haloperidol 30–40 mg/day. | Mean duration: 7 days | 34 patients (32 males and 2 females) |

|

| Self constructed scale of full recovery or no recovery. | |||||

| Aliyev and Aliyev (2005) | Double blind randomized placebo controlled trial. |

| 7 | 40 male patients. 20 to drug and 20 to placebo | Sublingual glycine: partial remission: 20 (100%) |

| Placebo: no remission: 20 (100%) | |||||

| Aliyev and Aliyev (2008) | Double blind randomized placebo controlled trial. | Sodium valproate. | Initial dose titration 3. Total period 10. | 40 male patients |

|

| Starting dose of 100 mg/day, increased to 300 mg. | |||||

| Clinical Global Impression improvement scale. |

| ||||

| Aliyev et al. (2011) | Double blind, randomized placebo controlled trial. |

| 10 |

| Lamotrigine: partial remission: 20 (100%) |

| Placebo: no remission: 20 (100%) | |||||

| Aleksin and Egorov (2011) | Case series (Observational study)f |

| Unknown. | 26 males | Full remission: 24 (92%), Partial remission: 2(8%). f |

| Jordaan et al. (2012) | Case series. (Prospective open label non-comparative study) | 42 | 20 patients (16 males and 4 females) | Full remission: 18 (90%), partial remission: 2 (20%). |

| Author . | Study type . | Treatment and outcome measurement . | Duration (days) . | N, age range . | Outcome: no remission, partial remission and full remission . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gruenberg (1940) | Case seriesa | Electroconvulsive therapy wavelength 7.5 m; 15 min per treatment. Self structured scale of improvement or no improvement. | 5, 6 and 14 treatments. Maximum 28 daysa | Males 3; aged 28–40 | Full remission: 3 (100%)a |

| Bobrov (1966) | Case series (observational study) | Chlorpromazine, antidepressants, psychotherapy. | Unknown | 100 patients | No remission: 100 (100%) |

| Morales-Beda et al. (1968) | Case series |

| 56–252 | Males 6 | No remission: 6 (100%) |

| Entin (1970) | Case seriesb |

| 28–168 | 73 patients |

|

| Boriskov (1977) | Case series (Open label. observational study) | Antipsychotics, vitamin B1 (100–200 mg) and Biyohinol/ Bioochinolum preparation (quinine bismuth iodide) up to 40–50 ml. | 28 | 46 patients | No remission: 46 (100%) |

| Sampath et al. (1980) | Case series (Prospective observational comparison study) |

| Initial period-42 days. Then 546 days. | 30 patients with alcoholic hallucinosis (ICD-9 criteria) compared with 30 patients with paranoid schizophrenia | Alcoholic hallucinosis:

|

Paranoid schizophrenia:

| |||||

| Kabeš (1985)c | Double blind randomized placebo controlled. Crossover trialc |

| 6 | 24 male patients (16 withdrawal states and 8 alcohol hallucinosis) |

|

| Vencovsky et al. (1985) | Case seriesd |

| 2–3 | 35 patients (21 delirium tremens and 14 alcoholic hallucinosis) | Alcoholic hallucinosis: Full remission: 8 (57%). No remission: 6(43%) following parenteral treatment.d |

| Vicente et al. (1990) | Case series |

| 18–35 | 25 (23 males and 2 females) |

|

| George and Chin (1998) | Case seriese | Diazepam 30–40 mg/day. Vitamin B1 (1 ampoule/day) for 3 days, then 200 mg/ day. Haloperidol 30–40 mg/day. | Mean duration: 7 days | 34 patients (32 males and 2 females) |

|

| Self constructed scale of full recovery or no recovery. | |||||

| Aliyev and Aliyev (2005) | Double blind randomized placebo controlled trial. |

| 7 | 40 male patients. 20 to drug and 20 to placebo | Sublingual glycine: partial remission: 20 (100%) |

| Placebo: no remission: 20 (100%) | |||||

| Aliyev and Aliyev (2008) | Double blind randomized placebo controlled trial. | Sodium valproate. | Initial dose titration 3. Total period 10. | 40 male patients |

|

| Starting dose of 100 mg/day, increased to 300 mg. | |||||

| Clinical Global Impression improvement scale. |

| ||||

| Aliyev et al. (2011) | Double blind, randomized placebo controlled trial. |

| 10 |

| Lamotrigine: partial remission: 20 (100%) |

| Placebo: no remission: 20 (100%) | |||||

| Aleksin and Egorov (2011) | Case series (Observational study)f |

| Unknown. | 26 males | Full remission: 24 (92%), Partial remission: 2(8%). f |

| Jordaan et al. (2012) | Case series. (Prospective open label non-comparative study) | 42 | 20 patients (16 males and 4 females) | Full remission: 18 (90%), partial remission: 2 (20%). |

aAssuming maximum of two treatments per 7 days. Although 2 or more treatments could occur in a day.

bUnknown regimen. Original sample n = 204. Mixture of delirium tremens, organic brain syndromes and AIPD. Relevant AIPD cases examined.

cAssuming that three participants withdrawn due to severity of withdrawal state and subsequently requiring antipsychotics.

d29 patients had full remission. It is assumed that all 21 patients with delirium tremens had full remission.

e28 of 33 patients had complete remission. However, the adjustment of removing one patient is because this patient had delirium tremens and is assumed to have had full remission.

fOriginal mixed study (clearly defined cases of delirium tremens, AIPD, Korsakov’s syndrome and other psychiatric disorder due to alcohol and psychostimulants) of n = 125.

Treatments and Outcomes in AIPD studies

| Author . | Study type . | Treatment and outcome measurement . | Duration (days) . | N, age range . | Outcome: no remission, partial remission and full remission . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gruenberg (1940) | Case seriesa | Electroconvulsive therapy wavelength 7.5 m; 15 min per treatment. Self structured scale of improvement or no improvement. | 5, 6 and 14 treatments. Maximum 28 daysa | Males 3; aged 28–40 | Full remission: 3 (100%)a |

| Bobrov (1966) | Case series (observational study) | Chlorpromazine, antidepressants, psychotherapy. | Unknown | 100 patients | No remission: 100 (100%) |

| Morales-Beda et al. (1968) | Case series |

| 56–252 | Males 6 | No remission: 6 (100%) |

| Entin (1970) | Case seriesb |

| 28–168 | 73 patients |

|

| Boriskov (1977) | Case series (Open label. observational study) | Antipsychotics, vitamin B1 (100–200 mg) and Biyohinol/ Bioochinolum preparation (quinine bismuth iodide) up to 40–50 ml. | 28 | 46 patients | No remission: 46 (100%) |

| Sampath et al. (1980) | Case series (Prospective observational comparison study) |

| Initial period-42 days. Then 546 days. | 30 patients with alcoholic hallucinosis (ICD-9 criteria) compared with 30 patients with paranoid schizophrenia | Alcoholic hallucinosis:

|

Paranoid schizophrenia:

| |||||

| Kabeš (1985)c | Double blind randomized placebo controlled. Crossover trialc |

| 6 | 24 male patients (16 withdrawal states and 8 alcohol hallucinosis) |

|

| Vencovsky et al. (1985) | Case seriesd |

| 2–3 | 35 patients (21 delirium tremens and 14 alcoholic hallucinosis) | Alcoholic hallucinosis: Full remission: 8 (57%). No remission: 6(43%) following parenteral treatment.d |

| Vicente et al. (1990) | Case series |

| 18–35 | 25 (23 males and 2 females) |

|

| George and Chin (1998) | Case seriese | Diazepam 30–40 mg/day. Vitamin B1 (1 ampoule/day) for 3 days, then 200 mg/ day. Haloperidol 30–40 mg/day. | Mean duration: 7 days | 34 patients (32 males and 2 females) |

|

| Self constructed scale of full recovery or no recovery. | |||||

| Aliyev and Aliyev (2005) | Double blind randomized placebo controlled trial. |

| 7 | 40 male patients. 20 to drug and 20 to placebo | Sublingual glycine: partial remission: 20 (100%) |

| Placebo: no remission: 20 (100%) | |||||

| Aliyev and Aliyev (2008) | Double blind randomized placebo controlled trial. | Sodium valproate. | Initial dose titration 3. Total period 10. | 40 male patients |

|

| Starting dose of 100 mg/day, increased to 300 mg. | |||||

| Clinical Global Impression improvement scale. |

| ||||

| Aliyev et al. (2011) | Double blind, randomized placebo controlled trial. |

| 10 |

| Lamotrigine: partial remission: 20 (100%) |

| Placebo: no remission: 20 (100%) | |||||

| Aleksin and Egorov (2011) | Case series (Observational study)f |

| Unknown. | 26 males | Full remission: 24 (92%), Partial remission: 2(8%). f |

| Jordaan et al. (2012) | Case series. (Prospective open label non-comparative study) | 42 | 20 patients (16 males and 4 females) | Full remission: 18 (90%), partial remission: 2 (20%). |

| Author . | Study type . | Treatment and outcome measurement . | Duration (days) . | N, age range . | Outcome: no remission, partial remission and full remission . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gruenberg (1940) | Case seriesa | Electroconvulsive therapy wavelength 7.5 m; 15 min per treatment. Self structured scale of improvement or no improvement. | 5, 6 and 14 treatments. Maximum 28 daysa | Males 3; aged 28–40 | Full remission: 3 (100%)a |

| Bobrov (1966) | Case series (observational study) | Chlorpromazine, antidepressants, psychotherapy. | Unknown | 100 patients | No remission: 100 (100%) |

| Morales-Beda et al. (1968) | Case series |

| 56–252 | Males 6 | No remission: 6 (100%) |

| Entin (1970) | Case seriesb |

| 28–168 | 73 patients |

|

| Boriskov (1977) | Case series (Open label. observational study) | Antipsychotics, vitamin B1 (100–200 mg) and Biyohinol/ Bioochinolum preparation (quinine bismuth iodide) up to 40–50 ml. | 28 | 46 patients | No remission: 46 (100%) |

| Sampath et al. (1980) | Case series (Prospective observational comparison study) |

| Initial period-42 days. Then 546 days. | 30 patients with alcoholic hallucinosis (ICD-9 criteria) compared with 30 patients with paranoid schizophrenia | Alcoholic hallucinosis:

|

Paranoid schizophrenia:

| |||||

| Kabeš (1985)c | Double blind randomized placebo controlled. Crossover trialc |

| 6 | 24 male patients (16 withdrawal states and 8 alcohol hallucinosis) |

|

| Vencovsky et al. (1985) | Case seriesd |

| 2–3 | 35 patients (21 delirium tremens and 14 alcoholic hallucinosis) | Alcoholic hallucinosis: Full remission: 8 (57%). No remission: 6(43%) following parenteral treatment.d |

| Vicente et al. (1990) | Case series |

| 18–35 | 25 (23 males and 2 females) |

|

| George and Chin (1998) | Case seriese | Diazepam 30–40 mg/day. Vitamin B1 (1 ampoule/day) for 3 days, then 200 mg/ day. Haloperidol 30–40 mg/day. | Mean duration: 7 days | 34 patients (32 males and 2 females) |

|

| Self constructed scale of full recovery or no recovery. | |||||

| Aliyev and Aliyev (2005) | Double blind randomized placebo controlled trial. |

| 7 | 40 male patients. 20 to drug and 20 to placebo | Sublingual glycine: partial remission: 20 (100%) |

| Placebo: no remission: 20 (100%) | |||||

| Aliyev and Aliyev (2008) | Double blind randomized placebo controlled trial. | Sodium valproate. | Initial dose titration 3. Total period 10. | 40 male patients |

|

| Starting dose of 100 mg/day, increased to 300 mg. | |||||

| Clinical Global Impression improvement scale. |

| ||||

| Aliyev et al. (2011) | Double blind, randomized placebo controlled trial. |

| 10 |

| Lamotrigine: partial remission: 20 (100%) |

| Placebo: no remission: 20 (100%) | |||||

| Aleksin and Egorov (2011) | Case series (Observational study)f |

| Unknown. | 26 males | Full remission: 24 (92%), Partial remission: 2(8%). f |

| Jordaan et al. (2012) | Case series. (Prospective open label non-comparative study) | 42 | 20 patients (16 males and 4 females) | Full remission: 18 (90%), partial remission: 2 (20%). |

aAssuming maximum of two treatments per 7 days. Although 2 or more treatments could occur in a day.

bUnknown regimen. Original sample n = 204. Mixture of delirium tremens, organic brain syndromes and AIPD. Relevant AIPD cases examined.

cAssuming that three participants withdrawn due to severity of withdrawal state and subsequently requiring antipsychotics.

d29 patients had full remission. It is assumed that all 21 patients with delirium tremens had full remission.

e28 of 33 patients had complete remission. However, the adjustment of removing one patient is because this patient had delirium tremens and is assumed to have had full remission.

fOriginal mixed study (clearly defined cases of delirium tremens, AIPD, Korsakov’s syndrome and other psychiatric disorder due to alcohol and psychostimulants) of n = 125.

Treatment and outcomes in AIPD case reports

| Authors . | N . | Age (y) . | Sex . | Treatment . | Dosage per day (mg) . | Duration (days) . | Outcome . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bourdon (1956) | 2 | 50 | M | Chlorpromazine | Unknown | Unknown | No remission |

| Electroconvulsive treatment | 1 session | Full remission | |||||

| 55 | M | Electroconvulsive therapy | Unknown | 1 session | Full remission | ||

| Hytinnen (1987) | 1 | 35 | M | Haloperidol | Unknown | 6 | No remission |

| Chaudhury and Augustine (1991)a | 2 | 40 | M | Antipsychotics, vitamins, psychotherapy, supportive measures | Unknown | 56 | Full remissiona |

| 47 | M | Unknown | 168 | Full remissiona | |||

| Soyka et al. (1997)b | 1 | 33 | M | Haloperidol decanoate | 10 | 2190 | No remissionb |

| Perazine | 200 | ||||||

| Risperidone | 6 | 56 | Full remissionb | ||||

| De Millas and Haasen (2007) | 1 | 58 | M | Risperidone | 2 | 5 | Full remission |

| Alcohol abstinence | 4 | 56 | Full remission | ||||

| Kumar and Bankole (2010)c | 1 | 40 | M | Olanzapine | 20 | 10 | Full remissionc |

| Citalopram | 40 | ||||||

| Risperidone | 6 | 10 | Full remissionc | ||||

| Farcas (2012, 2016)d | 2 | 23 | M | Risperidone, benzodiazepines and vitamin B1 | 4 | 42 | Full remissiond |

| 43 | M | 4 | 42 | Full remissiond | |||

| Ogut et al. (2014) | 1 | 58 | M | Diazepam | 60 | Unknown | Full remission |

| Olanzapine | 10 | 19 | |||||

| Folic acid and vitamin B complex | Unknown | Unknown | |||||

| Bouritius et al. (2015)f | 1 | 38 | M | Quetiapine | 900 | 56 | No remissione |

| Flupenthixol | 18 | 56 | No remissione | ||||

| Haloperidol | Unknown | Unknown | Partial remission e | ||||

| Goyal et al. (2016)f | 1 | 59 | M | Trifluoperazine | 10 | 56 | No remissionf |

| Risperidone | 6 | 56 | No remissionf | ||||

| Clozapine | 200 | 56 | No remissionf | ||||

| Transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) | 2 sessions per day, 2 mA intensity | 5 | Full remissionf |

| Authors . | N . | Age (y) . | Sex . | Treatment . | Dosage per day (mg) . | Duration (days) . | Outcome . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bourdon (1956) | 2 | 50 | M | Chlorpromazine | Unknown | Unknown | No remission |

| Electroconvulsive treatment | 1 session | Full remission | |||||

| 55 | M | Electroconvulsive therapy | Unknown | 1 session | Full remission | ||

| Hytinnen (1987) | 1 | 35 | M | Haloperidol | Unknown | 6 | No remission |

| Chaudhury and Augustine (1991)a | 2 | 40 | M | Antipsychotics, vitamins, psychotherapy, supportive measures | Unknown | 56 | Full remissiona |

| 47 | M | Unknown | 168 | Full remissiona | |||

| Soyka et al. (1997)b | 1 | 33 | M | Haloperidol decanoate | 10 | 2190 | No remissionb |

| Perazine | 200 | ||||||

| Risperidone | 6 | 56 | Full remissionb | ||||

| De Millas and Haasen (2007) | 1 | 58 | M | Risperidone | 2 | 5 | Full remission |

| Alcohol abstinence | 4 | 56 | Full remission | ||||

| Kumar and Bankole (2010)c | 1 | 40 | M | Olanzapine | 20 | 10 | Full remissionc |

| Citalopram | 40 | ||||||

| Risperidone | 6 | 10 | Full remissionc | ||||

| Farcas (2012, 2016)d | 2 | 23 | M | Risperidone, benzodiazepines and vitamin B1 | 4 | 42 | Full remissiond |

| 43 | M | 4 | 42 | Full remissiond | |||

| Ogut et al. (2014) | 1 | 58 | M | Diazepam | 60 | Unknown | Full remission |

| Olanzapine | 10 | 19 | |||||

| Folic acid and vitamin B complex | Unknown | Unknown | |||||

| Bouritius et al. (2015)f | 1 | 38 | M | Quetiapine | 900 | 56 | No remissione |

| Flupenthixol | 18 | 56 | No remissione | ||||

| Haloperidol | Unknown | Unknown | Partial remission e | ||||

| Goyal et al. (2016)f | 1 | 59 | M | Trifluoperazine | 10 | 56 | No remissionf |

| Risperidone | 6 | 56 | No remissionf | ||||

| Clozapine | 200 | 56 | No remissionf | ||||

| Transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) | 2 sessions per day, 2 mA intensity | 5 | Full remissionf |

Please note: Outcomes dictate that an individual treatment episode occurred. Some patients received more than one treatment. Whenever more than one treatment is listed for a patient, the treatments listed were given consecutively.

aFull remission after 56 and 168 days. Time of response suggested to be immediate.

bFull remission occurred after a few days.

cDose of risperidone not specified. Assumed to be maximum doses, as per Joint Formulary Committee. (2015).

dFour milligrams refers to dose of risperidone. Unknown type, dose and duration of benzodiazepine. Confirmed by email correspondence from B. Masood to A. Farcas.

eDoses and duration not specified for quetiapine and flupenthixol. Assumed to be adequate therapeutic trial at maximum doses, as per Joint Formulary Committee. (2015).

fAuditory Hallucinations Rating Scale used.

Treatment and outcomes in AIPD case reports

| Authors . | N . | Age (y) . | Sex . | Treatment . | Dosage per day (mg) . | Duration (days) . | Outcome . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bourdon (1956) | 2 | 50 | M | Chlorpromazine | Unknown | Unknown | No remission |

| Electroconvulsive treatment | 1 session | Full remission | |||||

| 55 | M | Electroconvulsive therapy | Unknown | 1 session | Full remission | ||

| Hytinnen (1987) | 1 | 35 | M | Haloperidol | Unknown | 6 | No remission |

| Chaudhury and Augustine (1991)a | 2 | 40 | M | Antipsychotics, vitamins, psychotherapy, supportive measures | Unknown | 56 | Full remissiona |

| 47 | M | Unknown | 168 | Full remissiona | |||

| Soyka et al. (1997)b | 1 | 33 | M | Haloperidol decanoate | 10 | 2190 | No remissionb |

| Perazine | 200 | ||||||

| Risperidone | 6 | 56 | Full remissionb | ||||

| De Millas and Haasen (2007) | 1 | 58 | M | Risperidone | 2 | 5 | Full remission |

| Alcohol abstinence | 4 | 56 | Full remission | ||||

| Kumar and Bankole (2010)c | 1 | 40 | M | Olanzapine | 20 | 10 | Full remissionc |

| Citalopram | 40 | ||||||

| Risperidone | 6 | 10 | Full remissionc | ||||

| Farcas (2012, 2016)d | 2 | 23 | M | Risperidone, benzodiazepines and vitamin B1 | 4 | 42 | Full remissiond |

| 43 | M | 4 | 42 | Full remissiond | |||

| Ogut et al. (2014) | 1 | 58 | M | Diazepam | 60 | Unknown | Full remission |

| Olanzapine | 10 | 19 | |||||

| Folic acid and vitamin B complex | Unknown | Unknown | |||||

| Bouritius et al. (2015)f | 1 | 38 | M | Quetiapine | 900 | 56 | No remissione |

| Flupenthixol | 18 | 56 | No remissione | ||||

| Haloperidol | Unknown | Unknown | Partial remission e | ||||

| Goyal et al. (2016)f | 1 | 59 | M | Trifluoperazine | 10 | 56 | No remissionf |

| Risperidone | 6 | 56 | No remissionf | ||||

| Clozapine | 200 | 56 | No remissionf | ||||

| Transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) | 2 sessions per day, 2 mA intensity | 5 | Full remissionf |

| Authors . | N . | Age (y) . | Sex . | Treatment . | Dosage per day (mg) . | Duration (days) . | Outcome . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bourdon (1956) | 2 | 50 | M | Chlorpromazine | Unknown | Unknown | No remission |

| Electroconvulsive treatment | 1 session | Full remission | |||||

| 55 | M | Electroconvulsive therapy | Unknown | 1 session | Full remission | ||

| Hytinnen (1987) | 1 | 35 | M | Haloperidol | Unknown | 6 | No remission |

| Chaudhury and Augustine (1991)a | 2 | 40 | M | Antipsychotics, vitamins, psychotherapy, supportive measures | Unknown | 56 | Full remissiona |

| 47 | M | Unknown | 168 | Full remissiona | |||

| Soyka et al. (1997)b | 1 | 33 | M | Haloperidol decanoate | 10 | 2190 | No remissionb |

| Perazine | 200 | ||||||

| Risperidone | 6 | 56 | Full remissionb | ||||

| De Millas and Haasen (2007) | 1 | 58 | M | Risperidone | 2 | 5 | Full remission |

| Alcohol abstinence | 4 | 56 | Full remission | ||||

| Kumar and Bankole (2010)c | 1 | 40 | M | Olanzapine | 20 | 10 | Full remissionc |

| Citalopram | 40 | ||||||

| Risperidone | 6 | 10 | Full remissionc | ||||

| Farcas (2012, 2016)d | 2 | 23 | M | Risperidone, benzodiazepines and vitamin B1 | 4 | 42 | Full remissiond |

| 43 | M | 4 | 42 | Full remissiond | |||

| Ogut et al. (2014) | 1 | 58 | M | Diazepam | 60 | Unknown | Full remission |

| Olanzapine | 10 | 19 | |||||

| Folic acid and vitamin B complex | Unknown | Unknown | |||||

| Bouritius et al. (2015)f | 1 | 38 | M | Quetiapine | 900 | 56 | No remissione |

| Flupenthixol | 18 | 56 | No remissione | ||||

| Haloperidol | Unknown | Unknown | Partial remission e | ||||

| Goyal et al. (2016)f | 1 | 59 | M | Trifluoperazine | 10 | 56 | No remissionf |

| Risperidone | 6 | 56 | No remissionf | ||||

| Clozapine | 200 | 56 | No remissionf | ||||

| Transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) | 2 sessions per day, 2 mA intensity | 5 | Full remissionf |

Please note: Outcomes dictate that an individual treatment episode occurred. Some patients received more than one treatment. Whenever more than one treatment is listed for a patient, the treatments listed were given consecutively.

aFull remission after 56 and 168 days. Time of response suggested to be immediate.

bFull remission occurred after a few days.

cDose of risperidone not specified. Assumed to be maximum doses, as per Joint Formulary Committee. (2015).

dFour milligrams refers to dose of risperidone. Unknown type, dose and duration of benzodiazepine. Confirmed by email correspondence from B. Masood to A. Farcas.

eDoses and duration not specified for quetiapine and flupenthixol. Assumed to be adequate therapeutic trial at maximum doses, as per Joint Formulary Committee. (2015).

fAuditory Hallucinations Rating Scale used.

Trial studies

Four studies retrieved were double blind RCTs, of which one was a crossover study. One study included comparison with a group of participants with a diagnosis of paranoid schizophrenia. Ten studies were open label, non-comparative case series of treatment and outcome of AIPD.

Five of the included studies examined cases of AIPD arising in the context of alcohol withdrawal (psychotic symptoms started during the withdrawal state but persisted after other withdrawal symptoms had resolved). The trials are summarized in Table 1.

Types of treatment

Antipsychotics: No trials examined the use of second-generation antipsychotics. Six trials examined the use of single or multiple first-generation antipsychotics, including haloperidol, chlorpromazine, trifluoperazine, reserpine, thiotixene and levopromazine. Three trials examined the use of antipsychotics, benzodiazepines, vitamin B1 with treatment outcomes, but did not specify which antipsychotic drug was used.

Anticonvulsants: Anticonvulsants were used in three trials (lamotrigine, sodium valproate and phenobarbitone). Hypnotics such as barbamyl and chloral hydrate were used in one trial.

Others: Two trials examined other compounds that act on GABA receptors (piracetam and clorazepate).

One trial examined the primary use of an unusual treatment (glycine). One trial examined the use of electroconvulsive therapy (ECT).

Treatment results

There was marked heterogeneity of results, even with the same drug. For example, full remission rates for chlorpromazine varied from 0 to 68%, and partial remission rates from 0 to 32%. Better results with haloperidol included full remission rates of 68–90%, and partial remission rates of 0–30%. However, there were few trials of antipsychotic monotherapy, so findings are hard to fully interpret.

Heterogeneous outcomes were also evident in trials of non-antipsychotic treatments, apart from one trial of three patients treated with ECT, all of whom experienced full remission.

Treatment duration ranged from 3 to 546 days, but most trials were brief. Longer duration was not associated with more favourable outcomes. In three trials, duration was not stated.

Participants were predominantly male, as noted by Szefal and Zaleski (1983), who studied women with AIPD. Cohort sizes ranged from 3 to 100. Ten trials involved between 24 and 40 participants.

Case reports

The ten case report papers reported 13 separate patients who were exposed to 21 different treatments or treatment combinations. All patients were treated with first- or second-generation antipsychotics. Three patients were treated with adjunctive benzodiazepines and vitamin B1.

Treatments and outcomes are set out in Table 2. Outcomes were highly variable. Five patients experienced full remission with risperidone and two with olanzapine. No remission occurred in patients treated with chlorpromazine, perazine, flupenthixol, trifluoperazine or quetiapine. Of three treatment episodes with haloperidol, only one led to (partial) remission. There were two ECT treatment episodes, both of which were associated with full remission. However, it should be noted that the most recent report of ECT for AIPD was published in 1956.

Full remission was reported in one patient treated with transcranial direct current stimulation following failure of three different first- or second-generation antipsychotic drugs

DISCUSSION

Previous reviews of AIPD have focussed on aetiology, symptoms, prognosis and the relationship with schizophrenia (Soyka, 1994; Engelhard et al., 2015; Jordaan and Emsley, 2014). This is the first systematic review to examine treatment of AIPD. We included part of the non-English language literature, papers written in Dutch, French, German, Polish, Russian and Spanish. All papers were translated by P.L. or D.R. who are fully fluent in the respective languages, with the exception of Polish and Spanish where a translation service and Google translate were used respectively.

Main Findings

The findings of our systematic review are inconclusive. Studies generally had relatively low numbers of participants. There were few RCTs. Treatments were sometimes idiosyncratic, although these were usually supported by a rationale. For example, Aliyev et al. (Aliyev and Aliyev, 2005, 2008; Aliyev et al., 2011) justified their treatment with glycine, lamotrigine and sodium valproate by reference to Branchey et al. (1985), who suggest that amino acid abnormalities affect cerebral serotonin and dopamine levels and thus cause hallucinations. Their results do not support the use of these treatments. They reported high partial remission rates in RCTs but the trials were brief (10 days) with no indication of longer-term outcomes. High doses of medication were used. These may have caused sedative side effects, confounding findings of partial remission.

Overall, larger studies tended to report at least partial remission on antipsychotic medications, whether in combination with other treatments or as monotherapy. Some case reports concerned treatment with second-generation antipsychotics. Insofar as it is possible to tell, these appear to be no better or worse than older drugs.

Problems in studying treatments for AIPD

The sparseness of the literature is surprising, as alcohol dependence syndrome is common and AIPD is a serious complication of the condition. However, there are several problems in studying treatments for AIPD:

Firstly, it may be difficult to recruit and retain participants who are both alcohol dependent and suffering from psychotic symptoms. Prolonged abstinence can be difficult to achieve. Participants are likely to live in difficult social situations due to alcohol excess (Ali and McBride, 1997). These factors make compliance and retention in rigorous trials difficult.

Secondly, poor treatment outcomes in longer studies may lead to participants dropping out of trials. Underpowered trials generate inconclusive results.

Heterogeneous samples

The literature on AIPD and alcoholic hallucinosis has been dominated by attempts to ascertain whether there is a single syndrome, distinct from schizophrenia and delirium tremens, or whether there are several alcohol-related psychotic syndromes, either discrete or overlapping.

We found that all studies and case reports matched ICD-10 and DSM-5 criteria. All studies and case reports excluded clouding of consciousness as a key diagnostic criterion, which is congruous with DSM-5 and ICD-10 criteria. All case reports and studies described auditory hallucinations as a key feature in AIPD but some authors reported hallucinations in other modalities. Auditory hallucinations were second and third person, commentary, derogatory and command types. Delusions of persecution and of jealousy were reported in some participants. Boriskov (1977) described delusions of grandeur in AIPD, while Jordaan et al. (2012) found no evidence of significant delusions of grandeur. Interestingly, a few studies reported schizophreniform thought disorder (George and Chin, 1998; Vicent-Muelas et al., 1990). All authors reported that the onset of auditory hallucinations could occur during excess alcohol consumption or on alcohol withdrawal. No auditory hallucinations commenced during periods of extended alcohol abstinence.

The diagnosis of AIPD appears to have been stable in all studies. No changes of diagnosis to schizophrenia were observed. However, some participants experienced alcohol withdrawal symptoms, there was a wide range of psychopathology in different participants, and the timing of onset of AIPD was not always reported.

Attempts have been made to distinguish between AIPD and schizophrenia complicated (or precipitated) by alcohol misuse. In the 1950s, three large-scale studies followed patients with AIPD for 5–23 years in order to examine prognosis and diagnosis (Benedetti, 1952; Burton-Bradley, 1958; Victor and Hope, 1958). The conclusion was broadly similar: the majority of patients studied did not have schizophrenia. Cutting (1978) concluded from a study of 46 patients that AIPD could be regarded as an organic psychosis, and if there was any resemblance to schizophrenia this was due to an emphasis on Schneider’s first rank symptoms in earlier editions of ICD and DSM. He suggested that people with AIPD do not show features of schizophrenia as propounded by Bleuler (1911)—such as blunting of affect, autism, thought disorder and ambivalence—and by Kraepelin (1913).

A two part review by Glass (1989a,1989b) emphasized that schizophrenia and AIPD have different onsets, different symptoms and different outcomes. This view was shared by Soyka (1994), who had reported that patients with AIPD were more likely to have a family history of alcohol misuse than psychosis, and vice versa for patients with schizophrenia (Soyka, 1990). A number of family studies support a genetic distinction between AIPD and schizophrenia (Schukit and Winokur, 1971; Rimmer and Jacobsen, 1977; Kendler, 1985).

Case reports

These did not add significantly to our understanding of treatment strategies for AIPD. We found only ten case reports (Table 2). Treatment periods were usually around 56 days duration (Chaudhury and Augustine, 1991; Soyka et al., 1997; De Millas and Haasen, 2007; Bouritius et al., 2015; Goyal et al., 2016). Full or partial remissions occurred within a matter of days or not at all.

Remission on treatment with first-generation antipsychotics was common, but some reported success with subsequent use of second-generation antipsychotics, strengthening the suspicion of publication bias. Only one case report reported no treatment remission (Hytinnen, 1987). Case studies are well recognized to be potentially misleading, and we do not believe that any reliance should be placed upon them.

Non-pharmacological treatment strategies

In a very small number of cases, ECT and transcranial direct current stimulation appeared to be effective treatments (Gruenberg, 1940; Bourdon, 1956; Goyal et al., 2016). These findings are interesting but require replication in large studies.

There is a widely held clinical dictum that alcoholic hallucinosis does not resolve without complete abstinence from alcohol and that relapse of drinking tends to cause a return of hallucinations soon thereafter. Abstinence on its own was not an effective treatment for AIPD in one case report (De Millas and Haasen, 2007). Nonetheless, this is a safe treatment strategy, and it is surprising that there are no studies reported anywhere in the literature of alcohol withdrawal followed by complete abstinence with no drug treatment. This is a major gap in the evidence base.

Recommendations for future research

There is a prima facie case that the rubric AIPD is too broad to allow clear findings for treatment of different sub-types to be evident. This is evident in both DSM-5 and ICD-10 criteria. There is no evidence base to fall back on underpinning a pragmatic sub-classification. Although it is reasonable to conduct rigorous trials of treatment for a broad range of psychotic symptoms, we suggest that it would be helpful if future trials attempted to identify participants with relatively homogenous symptoms. The key variables to take into account are:

Did psychotic symptoms first arise during alcohol intoxication or, conversely, during acute alcohol withdrawal?

Are symptoms predominately hallucinations, delusions or both?

Is symptom duration one month, more than 1 month or more than 6 months?

Do symptoms persist during abstinence?

Is schizophreniform thought disorder present?

Greater clarity and homogeneity would distinguish, for example, participants who meet criteria for both schizophreniform psychosis and alcohol dependence syndrome from participants displaying a core ‘alcohol hallucinosis’ as described by Lishman (1998), with persistent vivid auditory hallucinations that arise with a quality of insight, but few or no other psychotic symptoms.

Clinical implications

Our systematic review suggests that there is adequate evidence that some patients with AIPD show a favourable response to antipsychotic medication. There is nothing to indicate the superiority of any particular drug. Both first- and second-generation drugs appear to be effective. However, it seems highly likely that many patients show little or no response to antipsychotics and that persistence when they fail to produce remission (whether partial or full) cannot be justified. There is no evidence to guide the duration of treatment. First principles would dictate that this should be as brief as possible, given the wide range of side effects associated with these medications.

As complete abstinence from alcohol, when it can be achieved, slows or stops other alcohol-related disease processes, there is good reason to strongly recommend it. There is sufficient weight of clinical opinion to caution patients that even controlled drinking may lead to the return of psychotic symptoms.

There is insufficient evidence for other treatments reviewed here to recommend their routine use in the treatment of AIPD

CONCLUSION AND LIMITATIONS

Given the relative dearth of data we chose a wide timeframe for our search. However, earlier papers may have included patients who may have been excluded if modern diagnostic techniques had been available. Furthermore, standard treatments such as antipsychotics were not available for a proportion of the early studies. Much of the evidence for treatment of AIPD is weak and is only level IV evidence (Agency for Health Care Policy and Research, 1992). The lack of research on AIPD may be due to a belief that it is easy to treat (Soyka et al., 1988; Jordaan and Emsley, 2014). However, this is mistaken as hospital readmission rates are high (Soyka et al., 2013). There is little clarity on how best to treat patients with persistent symptoms.

Heterogeneity is a problem in the studies found. We suggest that distinguishing between key variables of AIPD would help to understand the findings of future treatment trials. The evidence for the effectiveness of first- and second-generation antipsychotic drugs is based upon case reports and underpowered trials. Positive publication bias is likely. A funnel plot was not feasible due to the size and nature of the literature. There is supportive evidence to use this treatment, but better evidence is needed. Similar considerations affect studies using novel treatments such as GABA receptor compounds, but the lack of positive findings means that they cannot be recommended in the treatment of AIPD. Although some larger studies report the successful use of standard alcohol withdrawal treatments, longer-term management remains unexamined. There is an important gap in the literature on the management of patients whose symptoms fail to remit in response to antipsychotic medication.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank Nia Morris and Pauline Goodland from the John Spalding Library at the Wrexham Maelor Hospital for their valuable contribution.

FUNDING

There was no external funding provided for this project.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None declared.

DECLARATIONS OF INTEREST

All authors have no declarations of interest.

REFERENCES

- alcohol withdrawal syndrome

- ethanol

- heterogeneity

- antipsychotic agents

- psychotic disorders

- publication bias

- gaba receptors

- schizophrenia

- guidelines

- alcohol withdrawal hallucinosis

- diagnostic and statistical manual

- atypical antipsychotic

- international classification of diseases

- disease remission

- partial response

- first-generation antipsychotics